My, how poorly this country’s music industry and media have treated Kev Carmody. It’s not so much that Carmody’s work is undervalued – which it most certainly is – but that his artistry has been routinely misapprehended.

Carmody was over 40 years old when his first album, Pillars of Society, came out in 1988. It gained nods of approval from music critics and won over a variety of his contemporaries, including later collaborators Paul Kelly, Archie Roach and The Church’s Steve Kilbey. But much like 1990’s Eulogy (For a Black Person), 1993’s Bloodlines and 1995’s Images & Illusions, the record didn’t make the pervasive cultural impact that was warranted.

And so in the years since, despite an increasing number of lionising tributes (the foremost being this multi-disc compilation album), Carmody’s been assigned a load of inaccurate labels. Legacy act. Protest singer. Folkie. Troubadour. Indigenous artist. Each one of them too neat; too subjugating.

For starters, these labels fail to give you a sense of Carmody’s singularity and the manifest urgency of his songwriting. Protest is a recurring theme throughout his body of work and his experience as an Indigenous man who grew up during the Stolen Generations suffuses just about everything he sings. But he’s also a storyteller, an imagistic poet with an innate connection to the natural world, and an unvarnished vocalist with a knack for cramming the most unlikely words into a vocal melody.

Rolling Stone’s Bruce Elder called Pillars of Society “the best album ever released by an Aboriginal musician.” It sounds like high praise, but also carries the problematic implication that Indigenous artists are in competition with one another. And besides, why must their achievements be evaluated separately to the other artists releasing music in this country?

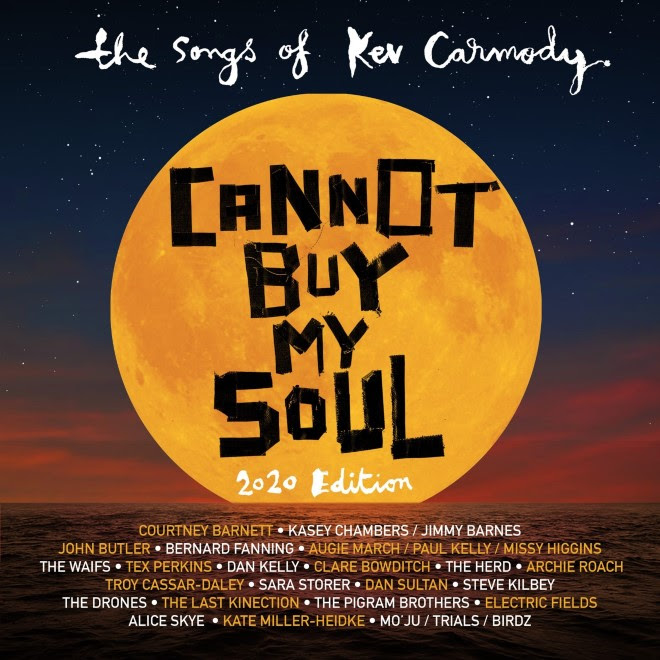

Cannot Buy My Soul is half tribute album, half best-of collection, which was first released in 2007. The original contained 16 cover versions from a range of singer-songwriters, bands and hip hop acts including The Waifs, Troy Cassar-Daley, Archie Roach, Clare Bowditch, Dan Sultan and The Herd. But disc two was the real drawcard as it brought together Carmody’s original recordings of the disc one selections. It’s all been preserved for the 2020 re-release, which also features six new tributes and the corresponding Carmody versions.

Once again, the inclusion of Carmody’s originals is essential as they’re representative of a body of work that’s very much alive and dangerous. It’s for this reason that a number of artists on the first half simply don’t stand a chance. You can’t really begrudge John Butler, Bernard Fanning or Kasey Chambers and Jimmy Barnes for falling short of the mark – sounding so out of their element, over-earnest, ill-matched – even if the curatorial decisions raise an eyebrow.

But the revamped Cannot Buy My Soul contains some true delights, such as Mo’Ju, Birdz and Trials’ overhaul of Bloodlines’ ‘Rider in the Rain’. Mo’Ju adapts Carmody’s first verse into a rousing chorus built around the line: “This road’s called ‘progress,’ it runs from oblivion to nowhere,” while Birdz uses the original lyrics as a springboard for his own reflections on the lies and hypocrisies of white Australia. Trials’ production deviates from the disturbed pace of the original to create an uplifting hip hop and soul number.

‘Blue You’, from the Kilbey-produced Images & Illusions, is brilliantly reinterpreted by Alice Skye. The loose, impressionistic original is an example of Carmody’s naturalistic poetic bent, and Skye’s version distils a vision of highway coasting, with the shimmer of hot desert land on view in every direction.

The Drones’ take on ‘River of Tears’ was a highlight from the original release. Carmody’s song provides a graphic retelling of the police killing of Indigenous activist David Gundy in his Marrickville home in 1989. It became a concert staple for The Drones in the years following its release and their version continues to induce a profound sense of heartache 13 years later.

Other standouts include Tex Perkins’ take on ‘Darkside’, a sprechgesang tale of squalor and misery rooted in the experience of the Logan kids who used to “hang out in that trashed out Rooster & Ribs.” And, in a manner akin to Mo’Ju and Birdz, both The Last Kinection and The Herd demonstrate that Carmody’s writing makes a great foundation for hip hop.

The Herd take on ‘Comrade Jesus Christ’, which appeared on Pillars of Society as a spoken word piece with no backing track. The song honours the legacy of Jesus Christ, but not in any conventional manner. Carmody refers to Christ as a “colonised Jewish man” who “spoke out against injustice” and attacked his self-righteous Roman oppressors. He was “one of the greatest humanitarian socialists” who’d be none too pleased, in Carmody’s reckoning, to see that the “very people he defied” have commercialised his birthday and perpetuated inequality in the name of profit across the globe.

It’s a macro version of the smaller stories that fill Carmody’s catalogue. All this talk about progress, and what do we have to show for it? The natural world is in active revolt and countries around the world are seeing greater income inequality than at any other time in modern history.

While not everything here hits the mark, Cannot Buy My Soul still manages to prove Kev Carmody is not just a subheading in the encyclopedia of Australian music; someone who ought to be politely lauded for his cultural contributions. He’s a freak, a weirdo, a rebel – and his work has never felt more necessary.

–