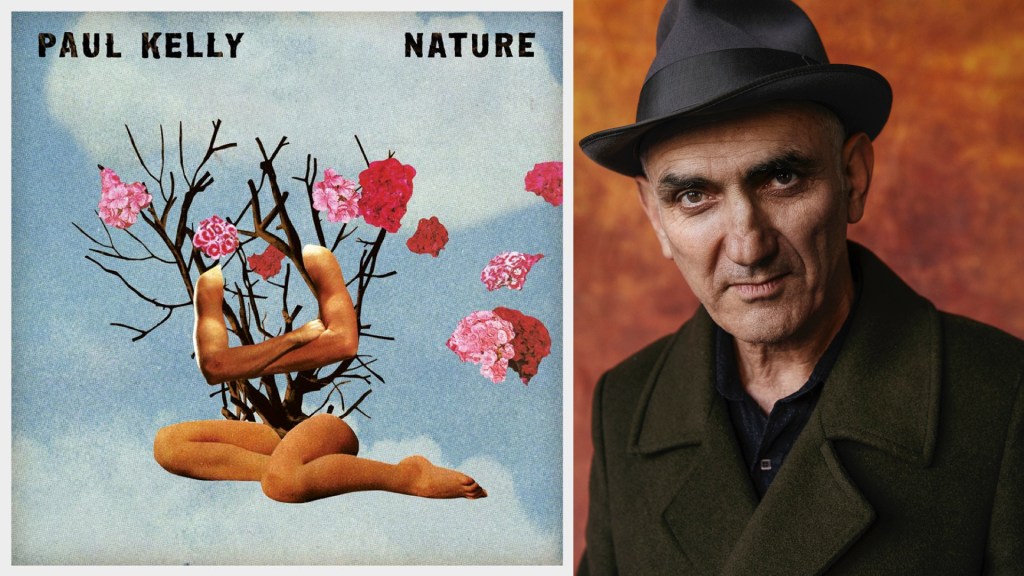

Paul Kelly’s reputation doesn’t rest in a single moment, and it certainly doesn’t rest with a single song. Broken lover, cricket fan, singer-songwriter or simply ‘the gravy man’ — take your pick, take as you can, take him as you will. Everybody has their own Paul Kelly.

For many, the bright sound of his 2017 album Life Is Fine was a…